Where We’re Putting Our Money

Atlanta, GA

September 7, 2022

September, as Mark Twain noted, is the most dangerous month to speculate in stocks…”along with July, January, April, November, May, March, October, June, December, August – and February.”

Since the Second World War, September is the only month with negative average market returns. But as we wade into dangerous seasonal waters, we’re also treading a treacherous change in the prevailing tide.

We’ve noted repeatedly how in 1913, with the establishment of the Fed, the monetary system got on the wrong track. Then, in 1971, it went off the rails.

By the late 1960s, the US government lacked real money to feed its fiscal furnace. The engine was suddenly incapable of pulling the guns and butter it had promised to haul. So central bank engineers opted to burn paper to keep the train going. For a few years, this kept things rolling.

But the bumps intensified, the smoke thickened, and the rattling increased. When champagne started to spill in the first-class bar car, elite passengers demanded to be let off the train.

The French were first. They wanted a refund on their diluted billet. But the US porter defaulted on his obligation by withholding their gold.

Then, on August 15, 1971, the head of the railroad sealed the safe. That night, Richard Nixon declared that no one’s ticket would be redeemed. They wouldn’t be taken where they were promised to go. Yet everyone’s gold would remain onboard.

The world was trapped on a ride it hadn’t booked, and had never been on. From that day forward, the monetary train lost touch with the ground.

Henceforth, the dollar would “float”, subject to the political whims of the men at the helm. Almost immediately, without the reliable guidance of sturdy rails, trust dissipated. On board, passengers noticed the cabins getting smaller, the portions shrinking, and the drinks being diluted.

After the dollar detached from gold, prices rose, wages stagnated, and the stock market tanked. In real terms, it fell almost 80% by 1982. As interest rates went thru the roof, bonds fell thru the floor.

There were few places to hide. Among the bunkers were real assets, energy, and precious metals. By the end of the decade, oil quadrupled, and gold rose twenty times.

It was then that Paul Volcker hopped onto the locomotive, blew the whistle, and applied the brakes. He pulled the lever fast, and far. The economy screeched to a halt.

The pile-up was extensive, and the damage severe. But it was a time of low debt that could absorb high rates. That is not the world we’re in today.

As passengers picked themselves up, brushed themselves off, and stumbled away, they swore they’d never again to be taken for a ride. But a new trip was about to begin.

In the early 1980s, equities were declared dead. Then, in the quiet dawn of a neglected cemetery, the bull market rose from the grave.

For several years, it wandered inconspicuous and unrecognized. Then, it got noticed. On an October Monday in 1987, it was brutally beaten and mercilessly mauled. When the carnage was complete, the Dow Jones Industrial Average…the face of the market…had lost almost a quarter of its teeth.

Fed dentists immediately stepped in, pumping monetary novocaine to repair the smile. It worked. And for four decades, whenever the market felt pain, central banks found more laughing gas…injected in the form of funny money.

After bubbles burst in 2000 and 2008, the Fed stepped in like bartenders to a hangover. Rather than “remove the punch bowl”, it spiked it. It tried to cure debilitating debt with additional credit.

The Fed nailed its funds rate to the floor, and began buying assets with counterfeit currency. And, superficially, this film-flam seemed once again to “work.”

But interest rates weren’t merely bound; they were also gagged. Without being able to speak, yields were unable to accurately convey the most important information a market needs: the price of credit.

Prices are more than numbers. They’re signals. They reveal not only which products are most demanded, but how resources should be allocated (across places, people, and time) to discover, design, develop, and deliver them.

When the Fed monkeys with interest rates, it blindfolds the economy, spins it around, and then puts banana peels along path where it encourages it to go.

Under these circumstances, markets (particularly with the Fed standing behind them) can stumble higher for a while (and often, as we’ve seen, for a long while). But at some point, they slip, and aren’t able to get up.

The effectiveness of phony credit wanes as debt levels rise. Steady drips of occasional morphine are no longer sufficient to dull the pain and keep spirits afloat. Manipulated markets needed greater doses of stronger stuff.

Like a drug-addled derelict moving from pot to heroine to get his fix, queered economies need weirder remedies to cure their ills. Like helium into a hot air balloon, “quantitative easing”, “zero-interest rate policy”, “Operation Twist”, financial bailouts, direct “stimulus” payments, and other hallucinogenic shenanigans floated financial assets on a steady flow of hot air.

For almost two generations, stocks and bonds were lifted higher by the incessant helium of artificial credit. By the third decade of this century, the global economy was high as a kite. The pandemic crimes of lockdowns and closures exacerbated artificial demand by constraining supply.

For years, moronic restrictions on hydrocarbons reduced exploration for reliable energy. Idiotic sanctions on Russian sources have made matters worse. Now, for the first time in forty years, the Fed is unable to inflate its popped balloon.

Markets, like nature, tend to move in slow sweeping cycles and long predictable waves. For four decades after the Second World War, interest rates rose, and bond prices fell. For the next forty years, they did the opposite.

Now, the primary trend has turned. Last summer, bond yields scraped 5,000 year lows. They’ve begun to move higher, and will likely keep going for the rest of our lives. We described some other recent cycles above, and will detail another one below.

On the surface, waves will continue to chop and churn. But beneath the surface the current has shifted. So how to stay afloat? When trying not to drown, what assets go overboard, and which stay in the boat?

(NB: we include real estate…and ideally a “bolthole”… as part of a well-rounded portfolio, but that’s more personal and local so have excluded it from this assessment)

Bonds

First the easy part: with one exception, no bonds.

For forty years, the tide has come in. Stocks and bonds rose together on an ocean of credit. Now, the undertow strengthens, debt is drying up, and stocks and bonds are both pulled down. This year, the “60/40” portfolio by which they’ve been tied together has sunk further than it ever has. The Fed, the full moon that kept the water rising, is waning. Without that buoyancy, bonds are reclaiming James Grant’s moniker of “return-free risk”.

Bonds are no longer a life vest. They’re an anvil. Their risk comes in three forms: default, currency, and interest rates. All are flashing red right now. With rising rates, bonds will lose value over time…as we’ve seen this year. And were the principal returned, it would be in a deeply depreciated currency. No thanks.

The only potential exception to this aversion are Series-I Bonds issued by the US Treasury. These currently yield over 9%, and rates adjust every six months in accordance with inflation. The US government won’t (explicitly) default, and the inflation-adjusted yield should mitigate deterioration of the principal that will almost certainly be returned. Each person can invest $10,000 annually in these bonds, plus up to $5,000 of any income tax refunds he might receive. This is the extent of our bond investments.

Gold

Now that we’ve plugged a hole, we acquire our anchor.

Gold performed exceedingly well during the 1970s, the historical period we seemed destined to revisit. It also outperformed stocks during the first two decades of this century. While the S&P 500 quadrupled from 2000 – 2022, gold is up almost six-fold. Gold fetches fifty times as many dollars as it did when the two were untethered. Stocks are up “only” 18 times (including re-invested dividends) since the gold window was closed.

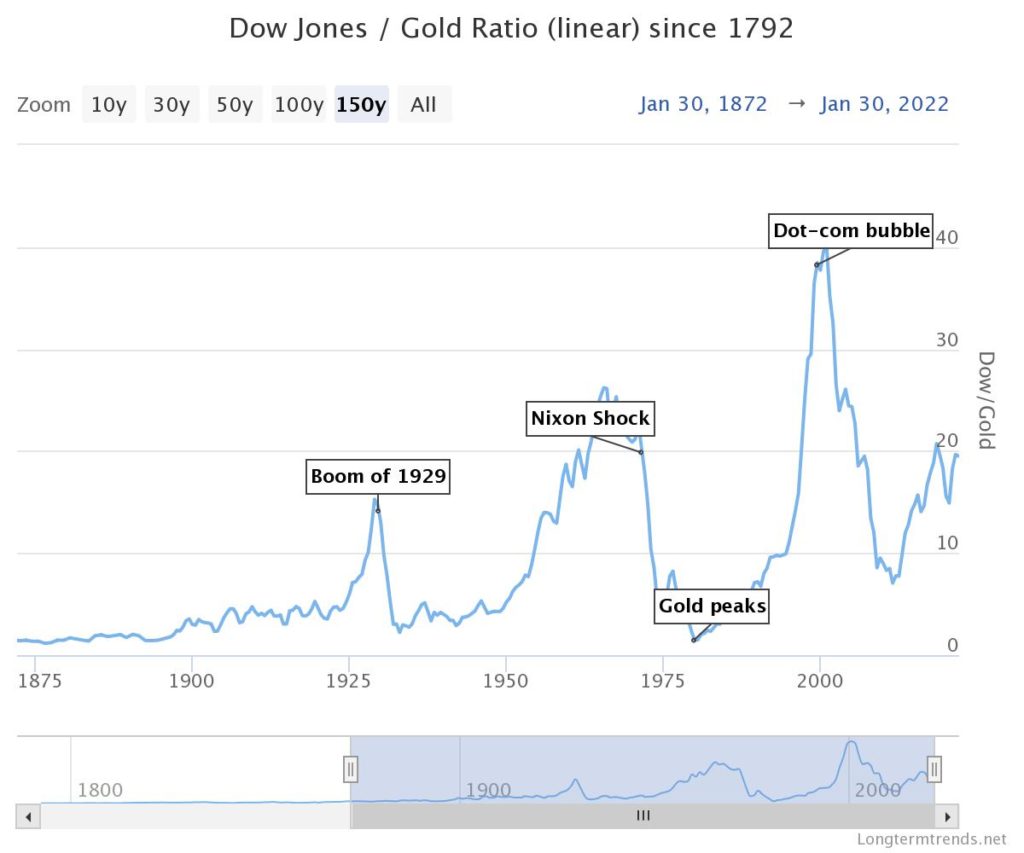

A vital addition to the crucial cycles and long waves we previously referenced is the “Dow-to-Gold ratio”. Bill Bonner and Tom Dyson use this measure…merely the Dow Jones Index divided by the price of an ounce of gold…as their compass. It uses real money to smooth out inflationary “noise” and better assess the value of stocks. When the ratio is high, stocks are expensive; when it’s low, they’re cheap.

We don’t use this tool to “time the market” or be too precise. As Bill Bonner put it, we’re not trying to hit the apple; we just want to ensure William Tell is pointed in the right direction.

The Dow peaked in 1929 at about 18 ounces of gold. That was the time to sell stocks and accumulate gold. A few years later, the ratio tanked to below two…a signal to exchange holdings of gold for inexpensive stocks.

For forty years the Dow climbed, exceeding twenty ounces in the late 1960s. The bell was ringing, and the top was in. Those who swapped stocks for gold avoided an 80% inflation-adjusted decline during the 1970s.

By the end of the decade, stocks were shunned, the Dow-Gold ratio approached one…and it was time to buy. For twenty years, the Dow went on a record run, and gold fell asleep (or into a coma). At the turn of the century, the ratio crested forty.

Everyone was in love with stocks, and disparaged gold. It was time get out of the market, and run for shelter. But few wanted to turn off the music or close the bar. Finally, in March 2000, the cops showed up. And over the following two years, heads pounded and nausea intensified as the hangover hit.

Except for those who sold stocks for gold before darkness set in. While stocks trudged higher into the ’08 financial collapse, gold multiplied four-fold. After the meltdown, the Dow-Gold ratio had fallen to six.

Then, for the next twelve years, the pendulum swung the other way. Last year, the ratio again touched twenty, and stocks began to fall. I think they have much further to go.

Regardless the ratio, I think it’s always worthwhile to own some gold. Certain periods require only a little. Others demand a lot. For my money, this is one of those “others”.

While gold lagged badly during the stock and bond bull of the late twentieth century, that is not the environment we are in today. Compared to current astronomic levels, debt twenty-five years ago remained relatively low, and real interest rates comparably high. Even after recent increases, today’s real rates (based on government data) remain submerged at negative six percent!

The Fed Funds rate would need to approach (or exceed) ten percent to surpass the current rate of official inflation. Public and private debt-levels of $90T (!) are way too high, and the economy far too fragile, for that to happen. So it won’t. Real rates will remain low (if not negative). Gold should thrive, and stocks (in general) should suffer.

The point with gold isn’t to increase our wealth. It’s to preserve it. Gold is money. That’s it.

As we endure the crisis, we merely want to retain purchasing power till we come out the other side. I’ve owned gold for years, and have always hoped its price would go down. That would imply most things are going well.

But I don’t think they are. And they seem to be getting worse. It’s time to bar the door and batten the hatches. And gold has always been the best latch.

Over the last couple years, as the storm clouds gathered, I’ve increased gold (including some silver) to 35% of the investment portfolio. We’ll keep it there till the Dow-Gold ratio sends a signal to reduce.

Stocks

Jeremy Grantham recently reminded us that stock markets act “normal” 85% of the time. But it’s the other 15%…when fear, greed, euphoria, or panic are in the saddle to guide the herd… that matter most. That’s where we are now, on the tip of a pin piercing what may be the greatest financial bubble of our lives.

For forty years, stocks and bonds have been the place to be. A demographic breeze has filled their sails, and Fed winds have pushed their backs. But now the pressure has shifted, clouds are forming, and gales are increasing.

Profitless goofball “growth” stocks that rose on hot air of easy money have plummeted during the deep freeze of contracting credit. Most haven’t hit ground, and have further to go. And given prevailing financial conditions, even “sturdy” stocks may be part of the avalanche.

With this in mind, why own stocks at all? Because we must guard against arrogance, and protect against being wrong. Despite a general aversion, owning some stocks is prudent, an act of humility. No matter how many stocks we think may fall, or how far we believe they’ll go, we don’t know for sure.

And as we saw in the 1930s and 1970s, some businesses do well when the world is in tatters. Others are strong enough to weather the storm, and prosper when it clears.

These are the type businesses we want to own now. They are solid companies with reliable profits and rising dividends, that produce real things: energy, agriculture, precious metals, maybe some utilities, healthcare, or consumer staples, and the best businesses that ship or store these essentials.

To provide more cushion and extra income, we usually sell put options to acquire desired stocks. And when selecting them, we embrace concentration by focusing on the best ideas to not dilute performance with over-diversification.

Yet for the time being our exposure to stocks is greatly reduced, with strict stop-losses for most holdings. As with gold, we should always own some stocks. There are times for more, and times for less. At our age and risk tolerance, this is a time for less. For regular income and targeted appreciation under anticipated conditions, a 30% allocation should do the trick.

Cash

In inflationary times, cash is a melting ice cube. But, at least for a while, it’ll keep our drink cold while the heat is on. Like a sealed freezer when the power goes out, cash can temporarily preserve the essentials while storm rolls by.

Inflation eats away the value of cash. But when everything else is falling off a cliff, I’d rather float slowly to the ground with the safety of a parachute. That’s what cash provides. It offers diversification, optionality, an ability to sleep, and time to think.

After markets crash and the smoke begins to clear, cash is the shovel that lets us sift thru the rubble for abandoned gems and forgotten heirlooms. We can use it to scoop up marquee names that few others are able to access. Then, we’ll hold them forever and collect the dividends.

Cash comprises about 30% of the current portfolio.

Speculations

Bear markets aren’t times to try to get rich. They’re periods when you do what you can not to become poor. But smart speculation retains a small spot in our anxious portfolio.

I consider Bitcoin less a pure “speculation” than an asymmetric bet that’s likely to pay off. I think it’s the real deal and everyone should own some. But it’s recently been highly correlated to the vulnerable Nasdaq, so till further notice we’ll stack our small portion in the “speculative” pile.

With it we include an allocation to true speculations like options, warrants, and private investments. In total, and particularly in this environment, we pour into this bucket no more than 5% of investable assets, with strictly limited position sizes.

Conclusion

Markets take long trips along winding roads. Accidents are to be expected, with detours along the way. But as we’ve seen, major undulations are infrequent, yet come with cyclical regularity.

We don’t know exactly when steep descents will appear or ascents reverse. But we have a general idea, and think we’re headed downhill now.

Regardless, asset allocation historically affects portfolio performance than stock selection does, so that’s what I’ve focused on here. It’s more important to be on the right bus than to pick the best seat.

But wherever you sit, be sure to buckle up. As Bette Davis said, it’s going to be a bumpy ride.

JD