Great Men

Atlanta, GA

January 18, 2021

This weekend marks the 35th anniversary of the first time a holiday honored Martin Luther King.

In 1983, the third Monday in January was designated by the US government as the official annual recurrence. It took effect three years later. Over the ensuing decade-and-a-half, states adopted the day at varying rates and to different degrees.

The effort to establish this holiday began soon after King’s assassination, and it was quite contentious…even after President Reagan signed the enabling legislation.

Many of the challenges were euphemistic diversions to distract from undeniable racial resistance. Yet even if the stated objections are acknowledged as legitimate, these considerations do not detract from King’s considerable courage or his commendable commitment to a righteous cause.

These characteristics and accomplishments are more than worthy of remembrance, respect, and honor. All men are flawed. Obviously, the purpose of this day…as with any occasion dedicated to an imperfect person…is to recall the virtues unique to one man, not the vices he shares with many.

My grandfather, as Executive Vice President of National City Lines, bore direct witness to King’s courage.

The Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) was established the afternoon of December 5, 1955, with Martin Luther King chosen as its leader. The organization formed in the wake of Rosa Parks refusing to yield her seat four days earlier, and after a successful bus boycott earlier that morning. But the fuse was lit years before.

When blacks were told to sit in the back of the bus, they weren’t simply consigned to seats in the rear. It was more degrading than that. They first had to go to the front, and pay their fare. They then had to step off the bus, walk to the back, and re-board.

One rainy day in 1943, as she did most mornings, Rosa Parks approached the bus. But on this occasion, she tried something different. She paid her fare, and immediately sought a seat. The driver ordered her to get off the bus and re-board in the back, in accordance with the city ordinance.

Parks complied. She retreated from the front, and stepped onto the wet pavement. She then walked in the rain to the rear door, where she prepared to board. Then, before she could do so…the bus drove away.

A dozen years later, on the fateful day for which she is justifiably famous, Rosa Parks again approached the bus. The driver was the same man who had stranded her twelve years earlier.

Parks took the front seat of the “colored“ section, but was told to move when the “white” rows filled and additional whites boarded. She refused. We all know what happened next.

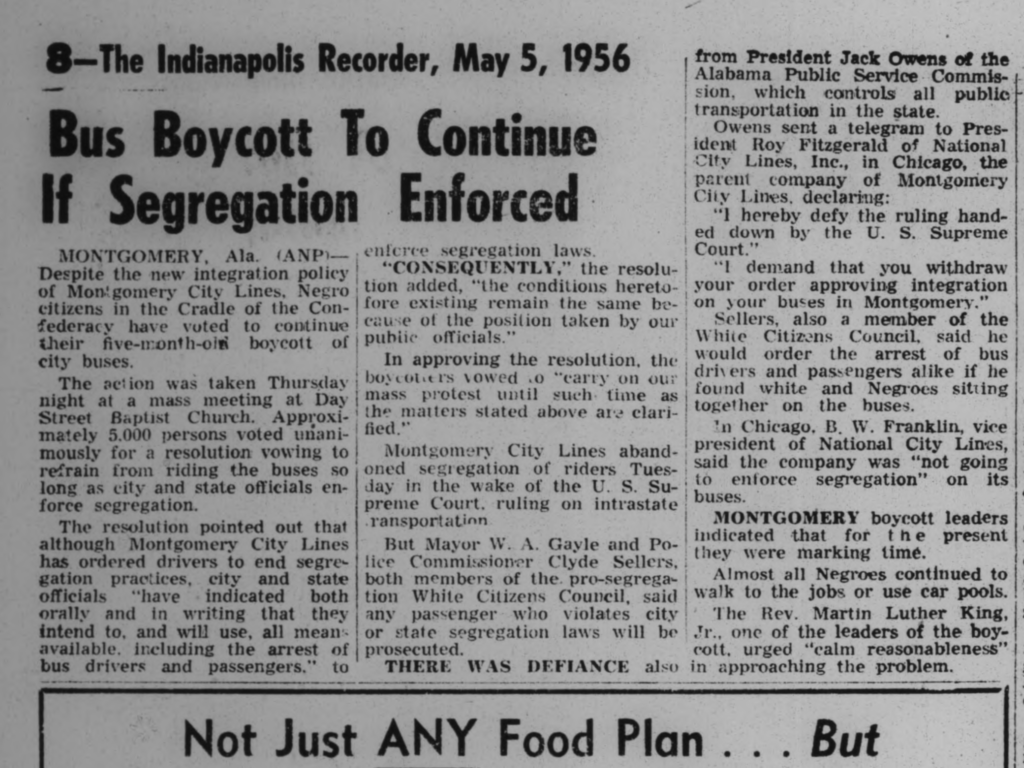

The MIA would orchestrate an ongoing boycott as part of a broader mission to “improve race relations…and uplift the tenor of the community.” The boycott would persist until their demands were met.

These conditions, as spelled out in a letter King wrote to National City Lines, were: courteous treatment by bus drivers, first-come-first-served seating, and employment of black bus operators in predominantly black neighborhoods.

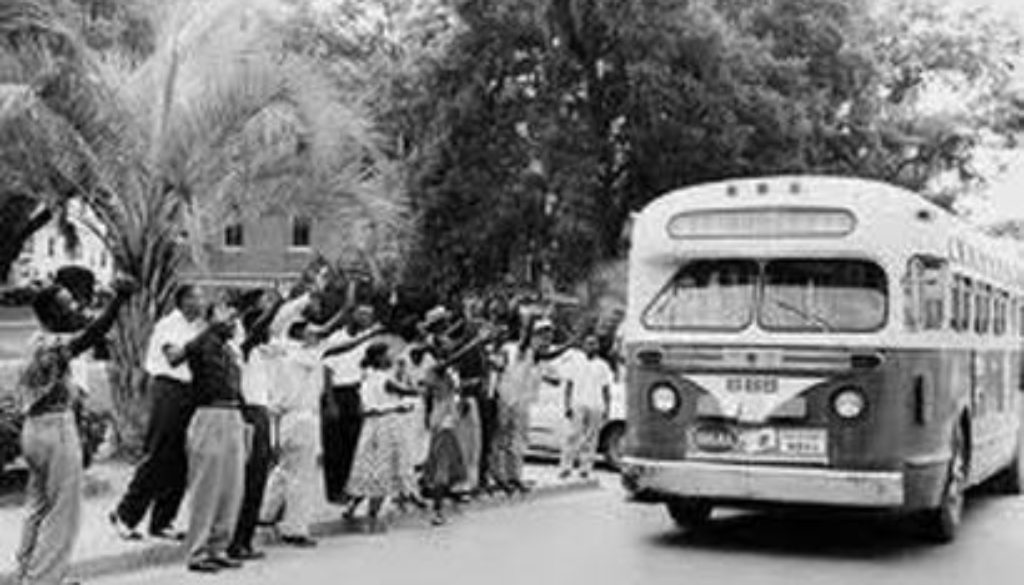

During the ensuing year, the MIA organized weekly gatherings to keep the black population mobilized, and daily carpools to keep them mobile.

At the meetings, attendees would pass the plate to sustain the boycott and finance legal challenges to city ordinances that segregated the buses.

Meanwhile, to stifle their efforts, the city deemed the carpools illegal because the private cars weren’t properly licensed. It also pressured insurance companies not to cover vehicles involved in the carpool. Black taxi drivers, who supported the boycott by reducing their rates to match the regular bus fare, were fined if they dropped their price.

King was relatively new to Montgomery and, according to Parks, was chosen to lead the MIA in part because he had yet to accumulate local enemies. That was about to change.

The month after the association was formed, his house was firebombed while his wife and young child were in it. Fortunately, neither were (physically) injured. But King’s admonishment to the crowd that gathered at his house just after the explosion…that they “love our enemies”…cemented his reputation for non-violent resistance.

National City Lines operated in cities around the country, so wanted no part of heated municipal controversies. This concern was particularly acute in Montgomery, where my grandfather tasked his Vice President, Ken Totten, with navigating not only the sudden boycott, but also the process of obtaining a new franchise from the city government.

Company President Roy Fitzgerald deferred to my grandfather in disputes with complicated legal elements, such as the one that had clearly materialized in Montgomery.

My grandfather joined National City Lines in 1938. Born in Anderson, South Carolina, raised in Augusta, Georgia, and recipient of both a Bachelor and a Law degree from the University of Georgia, he had a Southern pedigree that was beyond reproach. Fitzgerald assumed that such a background would help his Northern company traverse this tricky Southern terrain.

Based on recorded accounts, and my memory of what he told me, my grandfather assured King that the bus company had no desire to offend its customers, and was willing to work with him. But segregation was mandated not by the company, but by the state, so National City Lines could not unilaterally lift it.

King was empathetic…yet emphatic. He understood the bus line didn’t make the rules. But he also knew it had influence. That the influence would come from outside the insular realm of municipal Montgomery, from those not protective of local social status, could be of considerable benefit.

For his rôle in the boycott and instigating the carpools, King was indicted. Rather than wait to be arrested, he surrendered voluntarily, and spent two weeks in jail. This brought national attention, outside pressure and, within six months, a district court ruling that Alabama’s segregated bus laws were unconstitutional.

A couple days after the ruling took effect, a shotgun shattered the front door of King’s house. Bombings and beatings of local blacks escalated in coming months and years. Montgomery passed new orders requiring or reinforcing segregation. Even on board, despite the court order, fear and fatigue had returned most blacks to the back of the bus.

My grandfather told me these stories several years before he died. Till then, I was unaware of his rôle in the boycotts…or that he even had one. His admiration for King was clear in retrospect, but I imagine his feelings were more ambivalent at the time. If so, I wouldn’t be surprised.

He was a white businessman with southern roots. He was also an executive at a northern company with national reach. He was balancing the constraints of local law, his obligations to his corporation, and the perspectives that derived from his upbringing and surroundings.

He lived in Chicago when the boycott unfolded, but segregation was a way of life in many places. The South enshrined it officially in law; the North did so effectively in custom. Hearing him recollect the events in Montgomery from the distance of decades, I honestly think my grandfather did the best he could. In many instances, he did better than most.

My uncle informed me that at one point the head of the Alabama Public Service Commission…who also led the White Citizens Council (known otherwise as the KKK)…wrote my grandfather and ordered him to segregate the buses. In “polite legalese”, as my uncle put it, my grandfather replied with a suggestion that the commissioner stick his request somewhat further to the rear than the back of a bus.

A few years after the boycotts, my grandfather joined Martin Luther King for a visit to the offices of the local newspaper in Mobile, Alabama. King wanted more black drivers, and my grandfather was in agreement. But the policy could be successfully implemented only if it weren’t heavily publicized. Being a white southerner, my grandfather was better positioned than King to make that case to the local publisher. He did so, and the paper agreed not to print news of the hirings. They soon proceeded, and were successful…owing to the absence of what would otherwise have been a harsh backlash.

It’s easy to look back from the safety of our own time and think we would have done things differently than our ancestors did in theirs. I doubt it. Why would we? Most people at the time didn’t. What makes us so special? Who do we think we are? After all, look around. I think we will have plenty to answer for when our grandchildren reflect on us.

Would I have done any better in Montgomery than my grandfather did? I don’t know, but I have no reason to think so. I think he actually did pretty well. It’s easy to oppose segregation in 2021. In 1956, even (sometimes especially) among whites, doing so invited a firebomb in your kid’s bedroom.

More importantly, cultural attitudes were radically different, and were deeply embedded. Such ingrained perspectives, repulsive as we might find them, take time to change. Our predecessors changed theirs, and for that they deserve our empathetic credit rather than our supercilious condemnation. But they would not have done so without the courage and commitment of those…like Martin Luther King…who risked, and gave, their lives to effect that transformation.

My grandfather was a great man. Understandably, such men have faith in their judgment and confidence in their opinions. They don’t change them easily. After all, those are in large measure what got them where they are.

But they are also not impervious to influence, particularly when it comes from other great men. In Montgomery, my grandfather met such a man, and associated with him for several years. He said that he liked Dr King, that he was a good man and easy to work with. Slowly, perhaps imperceptibly…and possibly in ways he recognized only in the clear hindsight of later years…Martin Luther King influenced him.

As he did all of us.

January 22, 2021 @ 1:53 pm

JD, the article entitled ‘Great Men’ is very well written. Very interesting to learn all of the different aspects and sides that were in play back in those days. I could not imagine what it was like on any of the sides as you might say and I believe so many men did a great job traversing through this period.