Swedish Pancakes, Liberty Ships, and Dry Martinis

San Francisco, CA

June 1, 2011

Yesterday dawned cool and foggy. From our eleventh-floor windows, the marine mist obscured the view down Post Street, and covered the spires and banners above and around Union Square.

Down below, the clanging of cable cars announced the start of a new day in Baghdad by the Bay. In our small room, I awoke, somehow scampered downstairs without waking my wife and sons, and returned triumphant with two cups of coffee.

After Rita, Alexander, and David woke, we dressed, and made our way around the block. We expected to wait in line, but instead walked right into Sears Fine Foods. On Powell Street, just off the square and across from the Sir Francis Drake Hotel, this diner…despite a brief closure several years ago…has been a San Francisco institution for over seven decades.

The boys loved it, as do I. It is a tourist trap, but for good reason. The location is an obvious lure, but so is the nostalgic ambience of an old-time diner, and the satiating experience of a large traditional breakfast.

Few mornings are better than those featuring a pile of patented Swedish pancakes, a couple light scrambled eggs, several strips of bacon, and an endless stream of rich, aromatic coffee. Being amply fortified, our day was ready to launch.

Tho’ I once embedded myself as a proud San Francisco resident, I never let a condescending pride keep me from its wonderful places or appealing activities simply because tourists enjoyed them too. So, finishing our meal, we left one pleasant tourist trap, hopped on another, and made our way to a third.

From Sears, we caught the cable car at “Fantasy Island”, the small concrete median at Powell and Post. It received its colloquial appellation from the hordes of tourists who wait with persistent futility to board an endless concatenation of cars that pass fully laden with more proactive passengers.

But we caught a break. Noticing ample space on an approaching car, we jumped aboard, and were carried to the wharf. We found an exterior seat, the better enjoy the views and make the most of the ride.

Andrew Hallidie, a prolific builder of bridges and purveyor of wire rope, introduced in 1873 this unique mechanism for ascending Nob Hill. New lines were soon woven throughout the city, and replicated in others. With the profusion of the automobile, cable cars were rendered functionally obsolete, and disappeared from most cities.

Even in San Francisco, the web shrunk from its maximum expanse in the late 19th century to only three routes today. But to it the cash of enthusiastic visitors and casual commuters continues to stick. The clanging bells, the colorful operators, the undulating hills, and cross-streets offering spectacular glimpses of bay, bridge, and sky captivated our sons, and always bring a smile to their father’s face.

At the foot of Taylor Street, we disembarked. Before us was Fisherman’s Wharf, but that wasn’t our destination. We would come back later in the day to sample seafood stalls and souvenir kitsch. But first, we indulged more history.

By 1943, the situation was precarious. Across the bay, the Richmond Ship Yard cranked out almost 750 ships during World War II, a rate of production not equaled before or since. By the end of the conflict, it could deliver a Liberty Ship in less than two weeks.

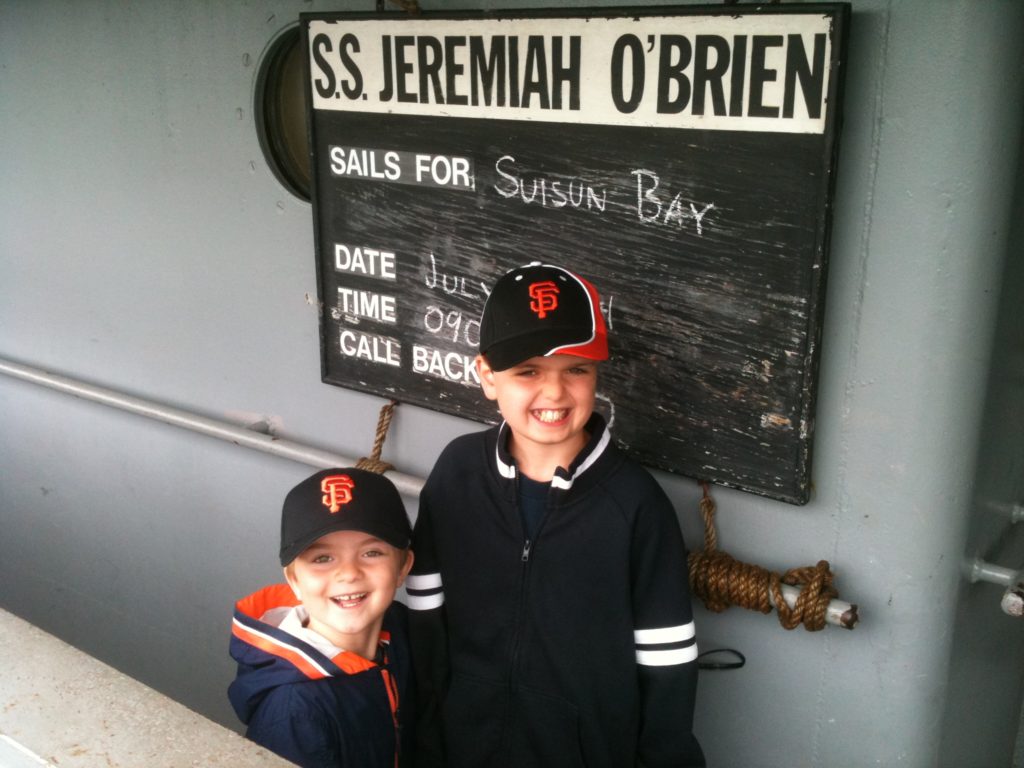

Across the country, near Portland, Maine, the New England Shipbuilding Corporation assembled one of its own. The Jeremiah O’Brien now bobs alongside Pier 45, beside the submarine USS Pampanito, in San Francisco Bay. The Pampanito made six patrols of the Pacific, sank as many Japanese ships, and damaged four more.

The Jeremiah O’Brien was among over 6,900 ships that gathered off the coast of France the morning of June 6, 1944. It made eleven trips back and forth across the channel to support and sustain the D-Day invasion.

Only five of the original 2,700 Liberty ships remain, and only two are unaltered. This is one of them. All the years I lived here and times I’d visited, I never toured the ship. Yesterday, I rectified that, and am glad Rita and our boys were with me.

From gangway to galley, thru hallways and along the deck, up to the flying bridge and down to the engine room, we caught a small glimpse of life at sea and the perils of war…aside, of course, from actually having to be in perpetual fear or on the precipice of death.

For Operation Neptune, the O’Brien carried men, food, ammunition, and jeeps for a landing that was by no means a predestined success. The ship somehow survived the bloody capture of Omaha Beach, finished the war plying the Pacific and Indian Oceans, and was afterward mothballed before reviving as a floating museum.

After a couple hours exploring the ship and the Omaha Beach Memorial Museum, we disembarked into the throngs crowding Fisherman’s Wharf.

The area that now teems with tourists initially enticed Italians. In the tide and wake of the Gold Rush, these inspired immigrants came from the mother country to pull metal from the earth and fish from the sea.

Like most of the neophyte miners and panners who flooded northern California in the mid-19th century, they found less luck with picks and shovels than with rods and reels. They hauled fish and crab from San Francisco Bay, and made homes amid the burgeoning Italian settlement along its shore.

As the wharf continues to accommodate fishermen, North Beach still evokes Italy. We wandered up Union Street, onto Kearny, and past the two-level flat where…in the shadow of Coit Tower…Rita and I once lived. We continued past the aromas and arias emanating from Caffe Trieste, along the cornucopia and cacophony of Columbus Avenue, over the crest of Nob Hill, and back to the Kensington Hotel.

After a quick dinner at the Pinecrest Diner, Rita and I took full advantage of our eleventh floor room by leaving it to our kids. Then, we went out for drinks.

The St Francis Hotel rose in 1904 on the west side of Union Square. A couple years later, the Great Quake spared the structure, but the subsequent fire gutted the building. It was rejuvenated within a year, and soon surrounded a great Magneta Clock that was installed in the lobby to honor the re-opening.

Much as, three decades later, San Franciscans would start meeting at the Top of the Mark, they began at this time to meet “under the clock”. Rita and I admired the grand master clock, the gilded ceiling, the crystal chandeliers, oak columns, and magnificent murals that grace this ornate lobby. Then we settled into the bar.

The Clock Bar is famous for its period themes, elaborate cocktails, and extravagant expenses. We sampled all three, and were not alone. The place was packed. Tourists on vacation, businessmen on expense accounts, and couples on dates surrounded the cozy table we were fortunate to find.

Over a couple hours we reflected on the day, how much I’ve missed this city, and how glad we were to be back. As we did so, the scene, several martinis, and my wife’s Mohito enlivened the evening.

We had forgotten to wonder whether our sons were still in their room.